|

| Photo by Rachel Roessler |

What’s the difference between notoriety and fame? Money.

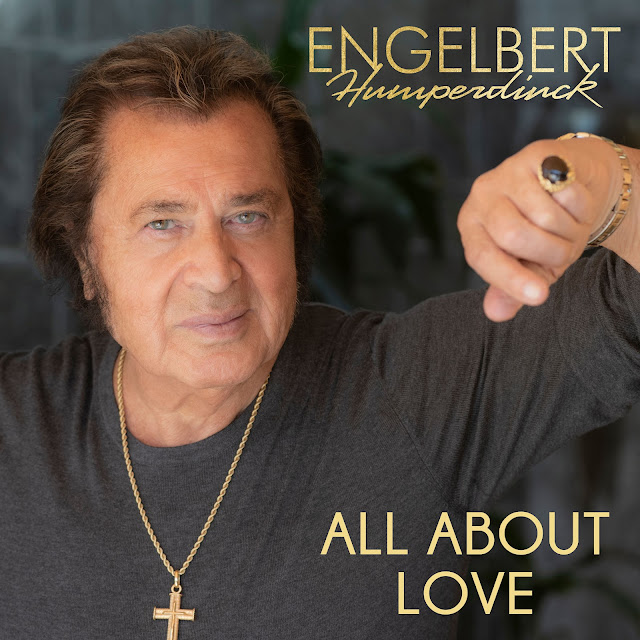

The above observation, paraphrased from a quote by the notorious Inger Lorre of The Nymphs, is one way to sum up where Los Angeles music mainstay/keyboardist/sonic alchemist Paul Roessler found himself 30 years ago. After first gaining notoriety in the late ’70s LA Punk scene as a member of The Screamers, he spent the subsequent decade building an enormous personal discography via his work with Twisted Roots, 45 Grave, DC3, Nina Hagen and others. Despite solidifying his place in underground music history, mainstream fame – and the financial rewards that came with it – eluded him. By 1993, he was a 35-year-old husband and father of two young boys – and a guy in need of steady cash. With royalties from indie labels and live gigs no longer providing what his family needed, Roessler found work as a handyman.

“I was trying to be a good dad and coach the kids’ basketball team, go to work every day and still do music,” he recalls. “I was very tired at the end of the day. I remember coming home – from getting up at six in the morning and working – and plopping down in front of the TV at five o’ clock and being exhausted.”

Meanwhile, Roessler’s wife, Helena – better known to Punk historians as LA scene legend Hellin Killer – had become what her then-husband calls “a very dramatic drug addict,” regularly going several days without sleep and having multiple run-ins with the law.

“I felt very trapped. We were very poor. She would drain our bank account, and the electricity would get shut off. It was fucked up.

“I would do all the things you’re not supposed to do,” he adds. “I would flush her drugs down the toilet, and I would bail her out of jail. I would make her out to be the bad guy. I had no understanding of the nature of addiction.”

Unfortunately, this lack of understanding led Roessler down a path that would define the next several years of his life.

“I made the conscious decision to use drugs to cope with the circumstances I found myself in. I thought, ‘I like drugs; why am I fighting this? What if I did it, too?’ Instead of this being a bone of contention, it would be something we did together. The secrecy and lying would go out, and I would manage it from the inside. It was probably the most codependent story you could imagine!”

With methamphetamine his chosen vice, Roessler hit the ground racing. Before long, he was working all day and creating new music all night – rest and mental health be damned.

“I would compose a piece of music at night. I would run off a cassette of it and then go paint houses for eight hours. I’d listen to that cassette over and over again and write lyrics for eight hours. It was pure creativity and salvation – and escape and processing sorrow and emotions. The drugs changed my personality and my voice. The music poured out like a flood.”

Roessler’s deep dive into questionable decisions coincided with a series of friends loaning him eight-track recording devices – a revelation for someone who previously had only four tracks in his garage setup.

“My life was hopeless, but I had eight tracks. (laughs) The drugs kept me going.”

This heightened activity was bolstered by Roessler’s preceding work with singer-songwriter Mark Curry, which included playing on Curry’s must-hear 1992 album, It’s Only Time (as well as on his 1994 follow-up, Let The Wretched Come Home). He credits Curry’s “incredibly painful, confessional music” as a major influence during this period.

“Mark was an astonishing talent who would do songs that would just make you weep, and he was so honest.”

Fueled by speed and stress, Roessler put down as much music as he could. And then… not much. Aside from a self-released 2003 album featuring 13 selected recordings made between 1993 and 1999 (more on that later) and a few demos posted on YouTube, the vast majority of Roessler’s addiction-era music sat unreleased for years.

That began to change during the pandemic. Like almost everyone else in the music business, Roessler suddenly found himself with some unexpected free time. He also had plenty of high-class audio equipment thanks to Kitten Robot Studios, the Los Angeles recording facility he’s co-owned for more than a decade. This combination led him to finally release the music he recorded alone from 1993 to 2001. Throughout 2021 (and leading up to the 20th anniversary of his sobriety), Roessler digitally released what is collectively known as The Drug Years – 65 songs spread over four double albums and five hours – on his Bandcamp page.

“Some of the stuff is exactly as it was recorded – straight off of DATs. Some of it was re-recorded completely. I tried to remix and occasionally re-record the songs over a 20-year period.”

Released in February 2021 (and featuring a guest appearance by Curry on the song “Eavesdroppin’”), the 18-track 12 Steppers And Dead Junkies represents the first two years of Roessler’s relationship with methamphetamine and sets the stage for the entire Drug Years listening experience.

“[The songs are] packed with sorrow, rage and madness,” Roessler writes on the album’s Bandcamp page. “Not all art has to be filled with those things; I don't demand that. These just come from a time in my life when that was mostly all I had to give. That said, I'm laughing at my predicament at least half the time.”

It could be argued (at least by this writer) that the album’s opening number, “Christopher Behind the 8-Ball,” unintentionally sums up the entire spirit behind The Drug Years in under four minutes. There’s certainly a sense of discovery felt in the song – after all, it’s a tune about Christopher Columbus written by a man who just began a journey into a new creative world through stimulants. That said, there’s also a helluva lot to unpack when the lyrics vaguely delve into a fictional scenario where Columbus gets cannibalized by his crew. This makes perfect sense, as Roessler was creating exciting new songs while slowly eating himself alive with methamphetamine. Despite this, he insists that he largely had his drug use under control.

“I had known methamphetamine addicts who seemed to handle it, so I was going to be that guy. I always thought it got me to where I needed to be. It gave me stamina, focus and emotional detachment. By some measures, I certainly wasn’t as presentable as I am now, but I always made sure that I slept and ate a certain amount. I wasn’t completely off the deep end.”

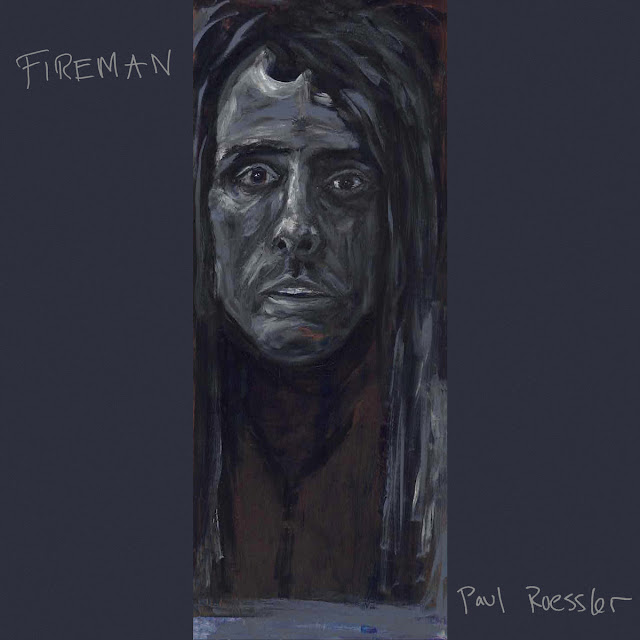

The second album in the Drug Years series, Fireman, arrived on Bandcamp two months later. Recorded in 1996 and 1997, the 13-song collection displays a heavy, Industrial-tinged vibe not unlike David Bowie’s album of the era, Earthling. Fireman’s many highlights include “Rolling Over” (originally released in an earlier form in 2002 via the soundtrack to the documentary Rage - 20 Years of Punk Rock, West Coast Style), “The End (Coming Together Nicely),” the wonderfully cacophonic “Peyote,” the Screamers-esque “Old People” and a cover of Bob Dylan’s “Highway ’61 Revisited” that sounds like it could have been recorded by D.o.A.- era Throbbing Gristle.

“It is my most Punk Rock album,” he says on Bandcamp. “Loud and wild. Funny and sad.”

Fireman makes great use of the Moog Opus 3 Roessler had previously played in 45 Grave. On Fireman, the synthesizer is distorted to kingdom come.

“When I was making [The Drug Years], I had no guitars, basses or drums. (laughs) I didn’t really have a computer either. I had to somehow concoct things.”

Roessler’s compositions during this period were informed in no small part by his mid ’90s stint as the live keyboardist for Prick, the group led by former Lucky Pierre frontman Kevin McMahon. Signed to Nothing Records (the label cofounded by Nine Inch Nails leader/former Lucky Pierre member Trent Reznor), Prick enjoyed a brief moment in the mainstream spotlight thanks to a stellar self-titled album in 1995 and time served sharing the stage with Nine Inch Nails. Roessler is quick to praise McMahon’s talents.

“He was basically [creating] Pop songs but with the production of Trent Reznor – like taking an Elton John song and mutating it into something really noisy, modern-sounding and cool.”

(Fun Fact: Roessler also played keys for Leah Andreone – best remembered for her ’96 Alt Rock single, “It's Alright, It's OK” – around this time. A search through YouTube will uncover a video of Roessler performing alongside future Marilyn Manson/Mötley Crüe guitarist John 5 in Andreone’s band on Late Night with Conan O'Brien.)

June 2021 saw the digital release of Boy Scout, 13 tracks that indicate that things were getting darker in Roessler’s world at the time of their creation.

As he writes on Bandcamp, “[A]s you can hear here, I had my rage. Rage at the homophobic Boy Scout organization and suburban parents. Rage at right-wing radio and Elvis Presley. Rage at addiction and sobriety. Rage at America and the Taliban. Rage at hope and God.”

The deceptively joyful “Self Helpless (Everybody’s Got To Make Their Own Mistakes)” plays like “Hey Jude” from Hell. While the song’s overall catchiness easily tempts the listener to sing along to the repeated earworm of “everyone’s gotta make their own mistakes,” what they are actually doing is indulging in a melody by a drug-addled songwriter who was refusing to accept help. The tune’s opening lyrics set the stage:

Madness set in June 9th, 1997

As foretold by every ex-junkie prophet that I know

And not one missed a chance to say they told me so

But the future is easy to read and the past, well, just watch it bleed

But today remains a mystery

All the local fools call me up down on their luck

And the geniuses down at the Alano club

Want to help me and tell me what to do

But I'd rather be dead than be like you

You say your life went out of control; well I gave up trying so long ago

And I think you're just looking for one more stone to throw, but...

Everybody's gotta make their own mistakes.

The date in the first line refers to a day when Roessler, while on the way to a rehearsal with original-era Los Angeles punks The Deadbeats, felt his brain playing tricks on him.

“I had been on drugs for about four years. I took the kids with me to practice. It was in the Valley, which is this horrible grid. We didn’t have cell phones then, and I was lost. That could happen to anybody, but at the time, I chose to use that as, ‘You’re losing your mind.’ Meanwhile, my wife had been in rehab and going to 12-step meetings, and I was getting my first taste of those through her. It was like, ‘I’d rather be dead than be like these people. Everybody’s got to make their own mistakes.’

“Helena got better before me,” he adds. “She would go to these rehabs, come out and be good for a couple of years. But at that point, I was on a roll. By the time I got to Boy Scout, which was probably ’98, we had been into this for about five years. She was doing better, but I was still in this creative frenzy. Like it is for all of us addicts, it was, ‘Life without drugs wouldn’t be that cool.’ So, I held on after she was doing better. She would backslide; she would have good times and bad times. It was not like she was consistently well, but she would have a year or two where she was okay. I would barge on.”

Roessler made “one of very few” attempts to kick methamphetamine while on a late ’90s tour as the keyboardist for The Joykiller, a band fronted by T.S.O.L. singer Jack Grisham. Although he succeeded in at least temporarily walking away from speed, he drank like a fish on the road. Before long, he was back to using it.

On New Year’s Eve 2001, Roessler finally decided to get sober – a change prompted by watching his younger son, Adam, struggle with addiction as well.

“He was following in my footsteps without nearly the suave, debonair sense of control that I brought to it. I’m being facetious! I always thought to myself, ‘Hey, man. If I die, so be it.’ I sort of had this moment of clarity; it was like, ‘What if you don’t die? What if he dies? How’s that going to be?’ It was such a frightening thought of going in and finding him dead. It wasn’t the idea of, ‘Oh, if I get sober, he’ll get sober and everything will be okay.’ It was more like, ‘If I don’t get sober, then I’m going to have to live with that.’ That was the wake-up.”

Not surprisingly, the initial weeks of this transition were far from smooth. Resurrecting his habit from the Joykiller tour, Roessler hit the bottle to fill the gap.

“I had done so much damage to my serotonin and dopamine receptors that I drank constantly for about a month to calm the anxiety and depression. Then, I reached the point where it was like, ‘Wow, I’m a better methamphetamine addict than I am an alcoholic, and I don’t want to be either one.’”

This is when he gave Grisham – who had already been sober for years – a call and asked for guidance.

“I had been on tour with him, and [he and others in The Joykiller] would go off to a 12-step meeting while I would sit back at the bar and drink. They would come back and go, ‘Oh, that was a great meeting.’ I remember thinking, ‘What the hell is a great meeting?’ They’d be all smiling and relaxed, and all the tension that had been in the band and in the van before they went was gone. That example stuck in my mind; I was like, ‘This does something to people when they do that. I’m gonna call Jack and figure out what the hell he’s doing.’”

Roessler has been sober since February 5, 2002. (In an interesting coincidence, his first conversation with this writer for this feature took place exactly 20 years later.)

“[Getting clean] was really an all-or-nothing thing. It was very clear in my mind; there was no going back. I had to think things like, ‘I may never write another song, but it doesn’t matter. Whatever the consequences of this decision, I’m going to live with it.’ I lost my edge and my creativity. I was exhausted and debilitated for years, and I came out of it slowly.”

Roessler released the fourth and final installment of The Drug Years, the 21-song Soft In A Hard World, on January 1, 2022 – two decades to the day he used methamphetamine for the last time. After the wild bender that was the previous three albums, the fourth chapter delivered the comedown.

“The theme of a lot of those songs is, ‘I’m sorry.’ There are a lot of apologies on that last record. Some of the songs were written before 1993; they were leading up to it. The reason why I think the song ‘Jealous God’ is so important is because I’m looking at Helena and describing this adoration of this crazy, crazy woman – which is what caused this whole fucking journey, but it’s written beforehand. And then the second song [“Still Life with Locomotive”] – ‘I’m turning to a life of crime’ – was written before that, too. I could feel myself falling into this. One song, ‘Risen,’ was written after.”

Soft In A Hard World’s intimate spirit is reflected in Roessler’s note on the release’s Bandcamp page:

“I am not singing to millions. I am singing to you and me, late at night, alone. It's supposed to make things a little better sometimes, for both of us. Maybe you felt like I felt when I sang these once. Isn't that amazing?”

All four albums in The Drug Years feature cover art by Roessler himself. The image that accompanies Soft In A Hard World is a surrealistic piece that displays Adam and his older brother, Alex, as small children with trumpets growing out of their noses.

“I read a book called Drawing On The Right Side Of The Brain. It’s very much about [the belief] that you don’t paint what you know; you paint what you see. My right brain was so open. Helena was doing a lot of art; sometimes, I would ask her to do a painting for me. She did some amazing stuff for me, but I started doing it. I did it for maybe two years, but then I thought, ‘Fucking music is more than enough to try to master in one lifetime!’ The paintings are so tied to that time; I’m really glad I had them.”

The first hint of what would eventually become The Drug Years arrived all the way back in 2003 via Curator: Selected Recordings 1993-1999, a 13-song CD that Roessler put out on his own.

“When I first got sober, a friend of mine had an idea to do a release. That’s the stuff I had [ready] at the time.”

One of Curator’s tracks, “Jade Buddha” (which can also be heard on Boy Scout) features a teenage Adam on guitar.

In 2006, Roessler published Eight Years, a chapbook of poetry inspired by the methamphetamine era, through Los Angeles’ Brass Tacks Press.

Sober and remarried, Roessler seems content to finally put the music that comprises The Drug Years in the past tense.

“Obviously, the circumstances of its creation are very personal. The emotions I was feeling throughout that period are laid out like a diary, but I also think the experiment of the influence of drugs – while it has been done before – is always an interesting lens.

“When I look at the art that I did before this experience, it’s a little trite and shallow. To me, the depth of soul and character that I started achieving in these works is of a different order – and I still had that when I came out of it.”

Roessler views the four double albums that comprise The Drug Years as one piece that is structured to invoke four basic phases of addiction:

1) The burst of well-being and creativity that the drugs initially bring

2) The chaos and drama that occur after the initial phase

3) The stasis that sometimes can occur if the second phase is survived

4) The final phase of suffering that eventually provokes recovery.

“The entire piece has that structure, and each of the albums contains that structure as well. Each album suggests four possible outcomes: The first ends in madness; the second, violence. The third ends in loneliness and isolation; the fourth ends in death. In my case, that person died, but a new person emerged.”

Roessler credits much of this rebirth to opening himself up to being around others as his recovery began to take shape.

“For me, discovering a community of other people was very medicinal. I’m a loner, and this is such an isolated journey. Of course, I had my family, but there was a lot of late-night isolation. To just sit in rooms with other people – plumbers, secretaries, CEOs of corporations, movie stars – and start to integrate back into society… You ask, ‘Well, how is that medicinal in getting over this hump of brain chemistry?’ Well, the brain has plasticity. Even at a neurological level, something about the community – and getting up out of your chair, getting in a car, driving to a place, shaking hands with people, seeing a familiar face, maybe making the coffee – helps the brain start to heal. I think I needed it. It’s not just that it kept me from doing drugs again, which I think it did, but you start to see a new horizon. It’s like, ‘I’m not going back to my old life without the drugs; I’m actually starting to see the makings of a new life.’”

Now in his 45th year as a working musician, Roessler is as active as ever. His most recent solo album, The Turning Of The Bright World, was released last July, while he continues to produce and record a variety of artists at Kitten Robot Studios. Not surprisingly, at least two double albums’ worth of unreleased material is left over from the Drug Years period and may see the light of day at some point.

Although he acknowledges that some positives came from his “huge, eight-year band-aid” of hard drug use, he is very quick to add there are healthier – and saner – ways to deal with life’s difficulties.

“The reason I’m sitting here talking to you is because I had extraordinary luck. There were 1,000 times when I could have been pulled over by the police. They could have looked in my wallet, and I could have done a lot of time. I was not 18 or 20, so I was more prepared for this sort of insane behavior, but it was still insane and dangerous behavior. I live with the brain chemistry repercussions to this day.

“I don’t want to demonize the drugs completely, because it’s silly. We all know drugs are great until they’re not. If you really use the drugs as the centerpiece of your life and your solution, ultimately they will take away as much as they give you. So, as I’m glorifying my drug use, let me drop caveats in the middle of it once in a while!”

Clearly, Roessler’s decision to finally release The Drug Years put a bright spotlight on an era of his life – and the lives of his loved ones – that wasn’t particularly pleasant. It was certainly a brave move, as it tempts the listener to wonder what became of the two children represented on the cover of Soft In A Hard World. Thankfully, their dad is pleased to report that both are doing very well and have been sober themselves for years. Described by Roessler as “deeply spiritual,” Alex is a computer programmer and cross trainer who lives in Maui. Adam lives in California and is an account manager for a large liquor distribution company. Additionally, he has a band called Igaf Sequoia, which his father has recorded.

“Both of my kids are doing incredibly well. They’re very, very successful, and they’re very wise and very content."

And what do Alex and Adam think of the events that spawned these albums now?

“My kids remember that period completely the opposite. Adam remembers it as, ‘Wow, what a traumatic childhood I had.’ Alex remembers it as, ‘What a wonderful, warm, tight-knit family we had.’ They both mean it.”

After conducting hundreds of interviews over the years, this writer has learned that most people desire two fundamental things regardless of their professions or passions: To be heard and to be understood. With that in mind, what does Roessler ultimately want people to hear and understand when experiencing The Drug Years?

“I have to stay out of that,” he replies. “There’s this thing about doing too much explaining; you kind of spoil people’s experience. I fucking called the thing The Drug Years, so I kind of showed my hand there. It does give people the opportunity to understand that this is coming somewhat from a place of madness, which is kind of a cool thing – Van Gogh’s cutting off his ear when he’s painting Sunflowers. Let people be aware of that.

“In my secret heart of hearts, I want people to listen to this and go, ‘Wow, eight albums!’ It’s like the entire output of David Bowie in the ’70s; it’s like the last five years of The Beatles’ career. ‘Oh, he plays all the instruments and writes all the music.’ I would like to have people see me as – as they say in sports – ‘the G.O.A.T.’ But what good is that? I’ve come to feel that is part of my illness and disease; the artist has to live in their own ego. For a year and a half while completing The Drugs Years and The Turning Of The Bright World, I had to live so in my ego – so about me. It’s exhausting. I never thought I would say this, but it’s going to be lovely to work on producing other people’s records again.”

Thirty years after jumping into the world of methamphetamine – and one year since making the sonic results of this misadventure available to the public – Roessler is both a survivor of his risky past and a creative force anxious to embrace the future. Above all, he is someone who remains unafraid to speak from his soul – either in conversation or through his unforgettable music.

“I really believe in the power of honesty. I flushed whatever career I was ever going to have down the toilet decades ago!” (laughs)

Paul Roessler on Bandcamp

Kitten Robot Studios

Kitten Robot Records

EMAIL JOEL at gaustenbooks@gmail.com